Churches were divided. Leadership was concentrated in the denominations. Believers eschewed cultural influence. Liberal modernism was on the move. Then God made Billy Graham.

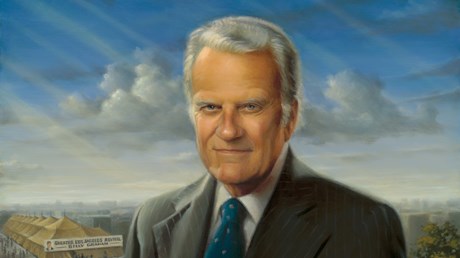

The first time Ruth Bell saw her future husband, he was dashing down the dormitory steps two at a time. Now there's a young man who knows where he's going! she thought. But in fact Billy Graham had no idea where he was going; no idea that he would travel the planet preaching the gospel to more people than anyone in history. Ruth's second impression, however, was spot on target: "He wanted to please God more than any man I'd ever met." This desire, more than anything, set him apart. In an era when evangelicals lived expectantly in the shadow of the Second Coming, Billy Graham was odd in hoping the Lord would tarry: "I sure would like to do something great for him before he comes."

The Lord did tarry, and Graham made the most of it. If there were a Mount Rushmore for English-speaking evangelists, Graham would be the fifth in granite, alongside Whitefield, Finney, Moody, and Sunday. For the most part, it's easy to imagine why huge crowds pushed and shoved to hear them preach. George Whitefield—short and cross-eyed, with the voice of a tornado—cavorted, posed, and wept on outdoor platforms as he brought Bible dramas to life. Charles Finney had terrifying eyes that drilled out soft spots in the soul, his fiery preaching about the wrath of God going straight to the exposed nerves. Billy Sunday was charming, with jazzy suits, movie-star looks, and a smile that lit up auditoriums. But up on stage, after joking and mugging and flattering the VIPs, he would throw down his hat, rip off his tie, and jump onto the pulpit—sometimes waving a large American flag—attacking sin and beseeching sinners to come to Jesus.

Dwight Moody's appeal is harder to figure. Of grandfatherly …

Source: Christianity Today Most Read