Why slaves adopted their oppressor’s religion—and transformed it.

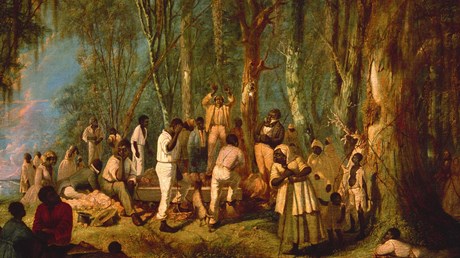

Peter Randolph, a slave in Prince George County, Virginia, until he was freed in 1847, described the secret prayer meetings he had attended as a slave. "Not being allowed to hold meetings on the plantation," he wrote, "the slaves assemble in the swamp, out of reach of the patrols. They have an understanding among themselves as to the time and place. … This is often done by the first one arriving breaking boughs from the trees and bending them in the direction of the selected spot.

"After arriving and greeting one another, men and women sat in groups together. Then there was "preaching … by the brethren, then praying and singing all around until they generally feel quite happy."

The speaker rises "and talks very slowly, until feeling the spirit, he grows excited, and in a short time there fall to the ground 20 or 30 men and women under its influence.

"The slave forgets all his sufferings," Randolph summed up, "except to remind others of the trials during the past week, exclaiming, 'Thank God, I shall not live here always!' "

It is a remarkable event not merely because of the risks incurred (200 lashes of the whip often awaited those caught at such a meeting) but because of the hurdles overcome merely to arrive at this moment. For decades all manner of people and circumstances conspired against African Americans even hearing the gospel, let alone responding to it in freedom and joy.

No time for religion

The plantation work regimen gave slaves little leisure time for religious instruction. Some masters required slaves to work even on Sunday. Even with the day off, many slaves needed to tend their own gardens, which supplemented their income and diet (others …

Source: Christianity Today Most Read