How the ordered nature of the fruit found its way into modern computing.

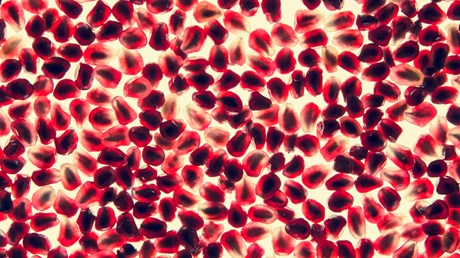

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), the talented astronomer whose work paved the way for Newton’s Law of Gravity, ate pomegranates with curiosity. Rather than simply eating the fruit mindlessly—as an animal might—Kepler was drawn to the shape of its seeds. He was intrigued by the fact that they tended to have 12 flat faces and wondered what the cause might be.

Is curiosity such as Kepler’s an essential ingredient of the human experience? Is there a longing for knowledge somehow hard-wired into us?

Aristotle might think so. More than 2,000 years ago, Aristotle described a clear distinction between humans and animals. We are, he says, unique when it comes to thinking about things—only humanity has any real “connected experience.”

As insightful as he undoubtedly was, Aristotle was beaten to the punch here. We can find the same assertion in a far earlier document—the biblical book of Job. In chapter 28, Job turns his thoughts to mining, and the search for treasures. Here, Job claims that the invention, insight, and curiosity of the human miners outshines that of the animal kingdom completely. When animals dig, it is pure survivalist instinct; when people dig, they “put an end to the darkness” and “bring hidden things to light.”

The Astronomer and the Seeds

Kepler’s interest in pomegranate seeds led him to some mathematical analysis. He decided that each individual seed would rather be a sphere, but that it was constrained and flattened by its neighbours as it the pomegranate grew. Twelve flat faces suggested a very particular configuration of seeds, and Kepler became convinced this was the most efficient way of getting spheres close together: “(This) …

Source: Christianity Today Most Read