Framing addiction as a chronic disease gives a broader framework for understanding.

I can’t remember much about the day when everything went wrong. No obvious moment indicated that the standard outpatient procedure would lead to weeks in the ICU, months in the hospital, and almost a year out of work.

Memories of a dark hospital room and slowly blinking lights come back in fevered fits. Dislocated voices from intrusive floating faces were saying that things would be alright.

I had known pain before: crutches, casts, and stitches. But until this moment, pain had always been experienced as something outside of myself. Now it was all that was left of me.

The day turned into night turned into day turned into night. I had given up on crying for the pain to subside. My soul had turned to the guttural moan of Job. Dear God, if this is my fate, may I never have been born at all.

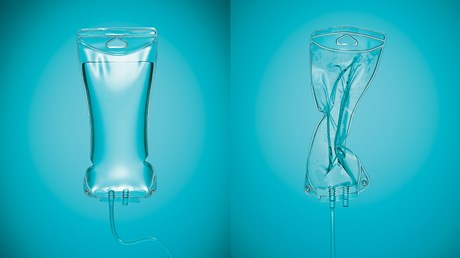

I remember hearing the words “acute respiratory distress” and being moved to the ICU. I remember how my IV stand became a tree that blossomed with multi-colored ornaments hanging from stainless steel branches with cascading ripples of wires and tubes falling to my nose, arms, and chest.

Also hanging there was a clear plastic box containing a small bag marked hydromorphone—an opioid pain medication. The only moments that I remembered I was still a person and pain was an experience I was having—and not my entire existence—was the moment every 15 minutes when I pressed a small button that sent a pump whirring and boosted the normally slow trickle of the blessed, blessed, blessed analgesic already flowing.

Over the course of this medical odyssey, my 5’ 10” frame dropped below 130 pounds, the whites of my eyes turned yellow, my stomach became distended, fevers spiked and dropped. There was vomiting, diarrhea, …

Source: Christianity Today Most Read